On about day 5, Cream Puff was bombarded by a flock of seabirds. The entire boat is covered in shit. It sounded like rain – A sign of things to come

Being at one with nature and the elements is remarkably calming and soothing. One feels a sense of peacefulness as the boat gently glides across the sea and rippling waves. We listen to Caribbean-style ska music or Jimmy Buffet and we sip rum concoctions in the evenings. During the day we bask in the sun topping off our vitamin D levels. We arrive at our destination fully relaxed and feeling refreshed ready to explore, shop, and dine in fine restaurants.

The previous paragraph is complete and utter bullshit. None of that is true. This is what the marketing departments of some boat manufacturers push out through media channels. If they told you what it was really like, they’d sell a lot fewer boats. The same is true with some vlogers or bloggers trying to build an image of a perfect getaway. They do this to build an attraction to the lifestyle so they can gain clicks and views which in turn generating ad revenue. They target the sad employee in the cube having a bad day and seeking a daydream of utopia. They tell them what they want to hear.

So, what is it really like? Here is a 30,000 foot view of what it is like to sail offshore on the ocean.

We focus on a list of 10 priorities while underway. I’ll talk about each in a little more detail. But for now, here is the list:

- Stay on (or in) the boat

- Keep the water on the outside of the boat

- Try not to get hurt

- Stay hydrated and nourished

- Rest and sleep whenever the opportunity presents itself

- Try to keep the boat going in the general direction of the destination

- Personal hygiene

- Make a list of things breaking on the boat to fix when the port is reached

- Hope it is not our time to die

- Have fun

On any passage, prior preparation is the key to success. Having backup systems and redundancy will ultimately save you stress, money, anxiety, and perhaps your life. Making sure everything works before setting off is top priority. When in Pape’ete Marina, the last weeks there kept me busy testing every system on the boat.

We were both looking forward to some time at sea. Our trip from Galapagos to Tahiti was near perfect conditions and sailing. We both hoped the same would be true for our trip to Fiji.

Our stop in Bora Bora was also meant to be used as a testing ground. Living on anchor, we are self-sufficient as we would be underway. This is our last chance to check our systems for issues. And, we discovered an issue. A big one.

On our first evening in Bora Bora, I cranked up our generator to charge our house batteries for the night. The house batteries consist of a series of deep-cycle batteries (meaning they are long-lasting and can be slowly drained – like a golf cart battery). These batteries keep things like the 3 refrigerator/freezer units running during the night when we don’t have solar power charging them. They also power all of our navigation systems, radio, lights, pumps, and fans etc. The generator started the first time as it always has. I turned on our large battery charger and the air-conditioning. It chugged and died.

Not wanting to take on a project that night and thinking daylight would be better suited to being in the engine room, we discovered we could run the large battery charger but the load of the air conditioning was too much. We just charge the batteries. I went to bed wondering what could have happened between Pape’ete, just a couple of days ago when it work just fine and now. This could be a deal killer for our planned trip.

The next day, I dive into the generator and discover a carbon buildup in the exhaust manifold. This is restricting airflow and doesn’t allow the correct mix of fuel and air for the engine to run efficiently. Once again, the diesel mechanic classes I took prior to embarking on this wacky adventure pay off. Without the correct air to fuel mix, it explains why it would die with a load on the unit. I put things back together again and fire it up. It’s not happy. It starts to blow out all sorts of smoke. So, is this a different problem or just the engine cleaning itself out now that it has airflow? I run it for a few hours. Slowly the exhaust clears up. However, I can see a tiny bit of diesel floating on the water. This is an indication that the fuel injectors need to be serviced. This is not critical but might explain why there was carbon buildup to begin with.

Now, the generator is working. But, there is still uneasiness in us because it died on us. How sure are we it’ll make it for the duration of our trip to Fiji? I convince myself we have a backup if the generator should totally die. We have a high-output alternator on our main engine perfectly capable of charging the house batteries. During the day, we have solar panels and a windmill generator. If we need to, we can turn off all the non-essential items and survive on solar. We decide not to abort and keep going.

As I address some of the list above, you’ll see what I mean. Writing this, we have just completed 1890 nautical miles (2175 miles / 3500 km) 15-days sail from Bora Bora in French Polynesia to Fiji. I made a few notes along the way. But, I’m having trouble reading my handwriting. We encountered some challenging conditions along the way and my penmanship suffered due to being limited to one hand. The other hand is always holding on to the boat.

I must stress, an ocean passage is not about being at one with nature. It’s more like dealing with what nature and Murphy decide to throw our way continually. Please don’t misunderstand, we have plenty of Zen moments where we think how lucky we are to be here and enjoy this. But, the Zen moment can rapidly disappear if a problem can’t be fixed.

On the first day of any passage, I go about the boat blasting anything that squeaks with T9. Blocks can be especially annoying underway. This is my last can from when we set out from Florida over 8 years ago.

Stay on the Boat

If a person goes overboard on a passage, the chances are overwhelming they will die. If you are at sea, you should drop an old pillow about the size of someone’s head (this is all you’d see of a person in the water) into the ocean and see how long it is visible. We’ve done this. On a calm day, you can see it for about 3 or 4 minutes. In normal or heavier seas, it’ll be visible for less than 30 seconds. Think about someone going overboard and the other person suddenly needs to lower sails and turn the boat in 30 seconds – it’s impossible. This is assuming, someone on the boat sees the other person go over. On most offshore trips, one of us is alone in the cockpit for the majority of the day.

Whenever we step out of the cockpit onto the deck, we ALWAYS wear a harness that attaches us to the boat. NEVER will one of us go on deck without the other watching them. Only on very rare occasions do we both go up on deck – both harnessed.

I’m happy to say on this trip, we both managed to stay aboard. Although, we had one particular night when I was a little worried. It was a very dark night. There was no moon or stars due to the light cloud cover. It had rained. The sea was very choppy and the swells were making the boat roll roughly from side to side. Cindy was asleep and I was alone in the cockpit playing cards on an awesome app cardgames.io. There was a massive bang followed by sails flapping loudly.

I didn’t need to wake Cindy up. She quickly realizes something is wrong and rushes to help. She found me turning on our deck floodlights and furling our mainsail. The jib was still flapping about and needed to be furled. Something has obviously broken but at this point, we don’t know what.

Prior to the bang, we’d been sailing along with a mainsail and jib poled out on a broad reach. To this day, I’m not sure what happened to cause this but, somehow the pole holding out the jib crashed into it’s stowed position up against the rail of the boat and no longer provided support for the sail. Nothing broke. It just miraculously moved even though it was held in place but 4 tight lines. This released the tautness of the jib sheet causing the jib to flap about. It’s amazing how a boat can be sailing along nicely with perfectly trimmed sails and just 2 seconds later all hell breaks loose. It takes us a few seconds to assess what to do next.

To get things back to normal, we find ourselves in a horrible situation. We are both up on deck at the same time (wearing a harness keeping us tethered to the boat). The decks are wet. It’s very dark. We’re tired. The weather is moderate and the boat is rolling from large swells hitting us broadside. This is one of those situations where things can go from bad to worse, quickly. Fortunately for us, it didn’t.

We take our time and move about slowly and deliberately also making sure to keep our center of gravity low. Once safely back in the cockpit, we both sigh with relief. Situation handled. Let’s not do that again anytime soon.

Keep the Water on the Outside of the Boat

This seems easy, right? Keep in mind; all boats are trying to sink. It is our job to slow that process as much as possible. And, there is the possibility, although a very minor one, that the boat could hit something putting a hole in it: A hole large enough to overwhelm the pumps.

Luckily the days of stepping into a life raft and trying to flag down passing ships for days on end hoping for a rescue have long since gone. I once read a book about a guy who abandoned ship and spent 76 days in a raft trying to flag down ships. Adrift: 76 Days Lost at Sea by Steven Callahan. To this day it remains one of the most boring books I’ve ever read. Day 1 – hit something and sank the boat. Day 2 through 75 – sat in the life raft waiting for a passing ship. Day 76 – Found by a passing ship. The end.

Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) have been around for a long time and make the events of the 1980’s Callahan book a virtual impossibility now. EPRIBs transmit via satellite a distress call that includes the position. They are inexpensive and do not require any type of monthly subscription. There is no reason whatsoever a person should be on the ocean without one. This is also why movies like All Is Lost, 2013 action drama film written and directed by J. C. Chandor and staring Robert Redford as a man lost at sea, is so incredibly unrealistic. A good prepared sailor will very rarely be lost at sea nowadays. Of course, I’m not saying it is impossible but I am saying the improvement in technology has made the chances much much less.

With today’s technology, rescue chances after abandoning ship are greatly improved. In a recent instance earlier this year, a vessel leaving the Americas bound for French Polynesia struck a whale and sank within 15 minutes from the time of impact. The crew did everything right. They set off their EPIRBs, radioed maydays, and launched their life raft and dinghy. The agency picking up the EPIRB signal notified their land contact who in turn posted the accident on various social media groups used by cruising sailors. Due to improved satellite technology, a message got to several small vessels near them and those with new Starlink internet technology were able to coordinate a rescue party. The crew of four was picked up after spending only one night in the raft.

Think about this: How cool would it be if Starlink added some software to their marine package that allowed a sort of “I’ve fallen and can’t get up” button. Starlink could easily send a message to all subscribing boats in the general area that a fellow sailor needs emergency help and give a position and contact information. {No charge for this idea Elon if you wish to add it.}

The above instance of a whale strike and fast rescue just a couple of years ago would not have been possible. Only larger vessels with expensive communication equipment would have been contacted and asked to render assistance. Internet at sea on small vessels remained stupid expensive. We have yet to add Starlink. The company seems to be working out the kinks but if we were starting out today this would be a no-brainer. But, there might be downsides to this.

I can’t help but think with this awesome new technology of high-speed connectivity at sea that we might see a new generation of ill-prepared sailors on the oceans. Are we heading to a time where we’ll see people sailing with their phones in front of their face all the time? Will they turn to Facebook groups and Gofundme options whenever they need help? Will they expect Amazon drones to drop engine parts to them in the middle of the ocean because they failed to plan ahead? Time will tell.

Having this special tool, a 70mm axle nut wrench save us from lots of grief. This fits the nut under the steering attachments to the square rudder post.

On our passage, I went to the aft head and found myself standing on a soggy carpet. Uh oh! Where did all this water come from? It didn’t take long to determine our rudder stuffing box was leaking. We were in very heavy seas for about 3 days. This puts immense pressure on seals such as the one in the rudder. There is really no way to test this ahead of a passage. The solution is to be able to fix it while underway.

I belong to many forums that discuss Amel boats (the Puffster is an Amel). On one of these groups a long time ago, someone mentioned having a special wrench (spanner) made. The stuffing box nut can be tightened but the wrench needs to be thin so as to fit under the steering connections. Rather than have a tool made, I found one on Amazon and purchased it. It is a 70mm axle nut wrench made by Tusk. This was about 10 years ago. It has remained in a plastic bag near the rudder post all this time awaiting for the day it might be needed. And voila, this was the day.

Having this special wrench and being prepared meant I could make a half-turn on the nut. This compressed the stuffing inside the box and stopped the leak. Else, the alternative would be to constantly mop up water in the aft cabin as a result of the leak. Or, perhaps I could disconnect the steering from the rudder temporarily – not something I would like to do at sea. A leak wouldn’t cripple us but it would make things stink. Seawater is smelly.

So, while underway after the nut was tightened and the leak stopped, I took a shop-vac to the rear and sucked up all the water out of the carpet. We hadn’t planned to clean the carpets while underway to Fiji but what the heck – making lemonade out of lemons.

Try Not to Get Hurt

There is no 911 or 999 out in the ocean. Well, there is if you are sinking or you need lifesaving medical help, but for everything else, you are pretty much on your own. Because of this, we carry a massive first aid kit. We also have a couple of books to use as a guideline in the event we need some help.Our favorite is: Where There Is No Doctor – A Village Health Care Handbook. By: David Werner, Carol Thuman, Jane Maxwell.

There are a lot of things that can hurt you on a boat. Using a sharp knife in rough seas is a no-no. Fingers can get caught in ropes. Booms can accidentally jive and knock a person off their feet, or worse. On day one of this journey we both got hurt.

Cindy stubbed her foot. Sometimes moving about can be very hard. I am reminded of a rag doll in a washing machine. Rough seas can be really dangerous and bang a person about. Even just sitting on the sofa can result in being tossed across the salon because of a rogue wave. It’s often a good idea to find a corner and wedge yourself in. Poor Cindy broke her little toe. Ouch! We didn’t need an x-ray to know it was broken. It was sticking out about 90 degrees from the other toes.

She reset the toe back into its proper position. Ouch! We used a popsicle stick and made a small splint. Think about the purpose of toes. They are to help you balance and stay on your feet. And, here is poor Cindy trying to move about on a floor that is pitching and rolling beneath her.

I managed to scold myself. I was preparing stew and was in the process of transferring the stew from the pot to bowls in the kitchen. It has been a while since we were last in big seas and we forgot to put our rubber non-skid mats on the countertops. Just as I had put stew into the bowls, a large wave rolled us violently and the bowl might have actually become airborne. I wound up with piping hot stew on my belly and not inside it. Ouch! I don’t think we’ll ever forget the non-skid mats again. I had a nice red burn mark for a few days.

Stay Hydrated and Nourished

It is hot during the day and cool at night. Think of the boat as like living in an RV or camper in the desert. Inside temperatures can be extremely uncomfortable during the day. With heavy seas, we have to keep all the windows closed as the spray will often cover the entire boat. This obviously adds to the interior heat.

On this passage, we faced some of the roughest conditions since committing to this lifestyle making eating more of a chore than a pleasure. The problem with longer passages is that weather is not an exact science. For a journey longer than 5 days, the forecast past the initial few days is a SWAG (scientific wild ass guess). We get weather along the way and will know what lies ahead. But, when we started out to Fiji, we expected about 12-15 days and had no idea what the second half would be like. Beginning on day 8, things got tough.

On this route, for the first time, we used a meteorologist to help for the second half of the trip. Cindy does a really good job with weather and has sort of made it a hobby. We figured a second opinion never hurts. On day 6, we received an email saying we had squalls ahead. This confirmed what we already knew was coming. We’ve had squalls before and have lived to tell the tale. But, this was different. It turned out there was a large system coming toward us and we had no way of avoiding it. For the next 3 days we were pounded by one squall after another after another. Our wind gauge goes up to 50-knots. It pegged there a few times. Mostly, the winds were 35 knots – sustained. Then it rained. I swear when the rain approached it sounded like a train coming. It was deafening.

We sailed for three days with a reefed jib (meaning the sail is furl with only a little bit of the jib in the wind). We took the brunt of the weather on the aft of the boat and slowed Cream Puff to just 5 knots to minimize the stress on the rigging and provide a better more comfortable ride for us. When the winds subdued to 25 knots it seemed calm to us. Most local boaters don’t sail in 25-knot winds as they consider it too windy.

Everything is wet. At one point I found myself sitting on a wet cushion, propped up with wet pillows in wet pants. I had a can of lemonade I was trying to drink without throwing up. I set it down for a second and it immediately became airborne and dumped itself on my burned tummy. I really didn’t care. It is on days like this we wonder why we are out here. Cindy coined a phrase, “this wouldn’t have happened if we’d been on a train”.

Rest and Sleep Whenever the Opportunity Presents Itself

Rest and sleep is precious. We don’t have a firm watch schedule. A lot of people ask about this. I will share what I have always said. People need to devise a plan around what works for them and not somebody else. What works for us probably won’t work for other sailors.

After supper, starting at about 4 or 5 pm (boat time), one of us will usually go for a rest. This is most often me. Cindy knows to wake me whenever she gets tired enough to sleep. Then, we swap. I keep watch and she’ll sleep. This goes on until about 10 am the next day (boat time). This is a 16-hour period during which we both try to grab 8 hours of sleep. This means on a journey like this we only see each other 33% of the time. The other 66%, one of us is sleeping, or trying to.

Good rest is hard with the rolling of the boat and noise. Because of this, we must be aware that we are tired and when we make decisions we should rethink everything. At one point, I noticed my very damp shirt was inside out. It had been that way for two days. I really didn’t have the energy to change it. It stayed that way until an opportunity presented itself to take a shower.

Try to Keep the Boat Going in the General Direction of the Destination

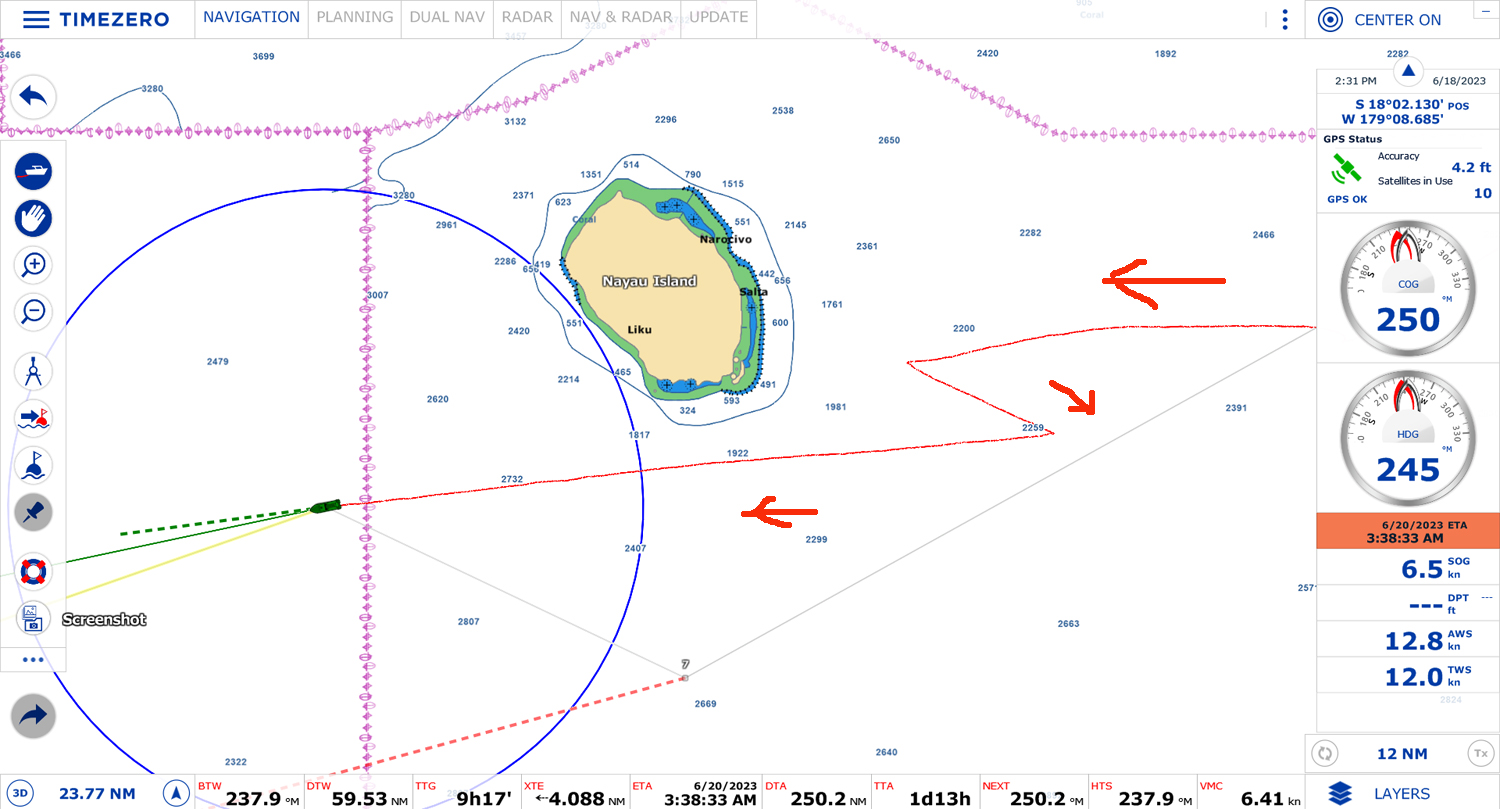

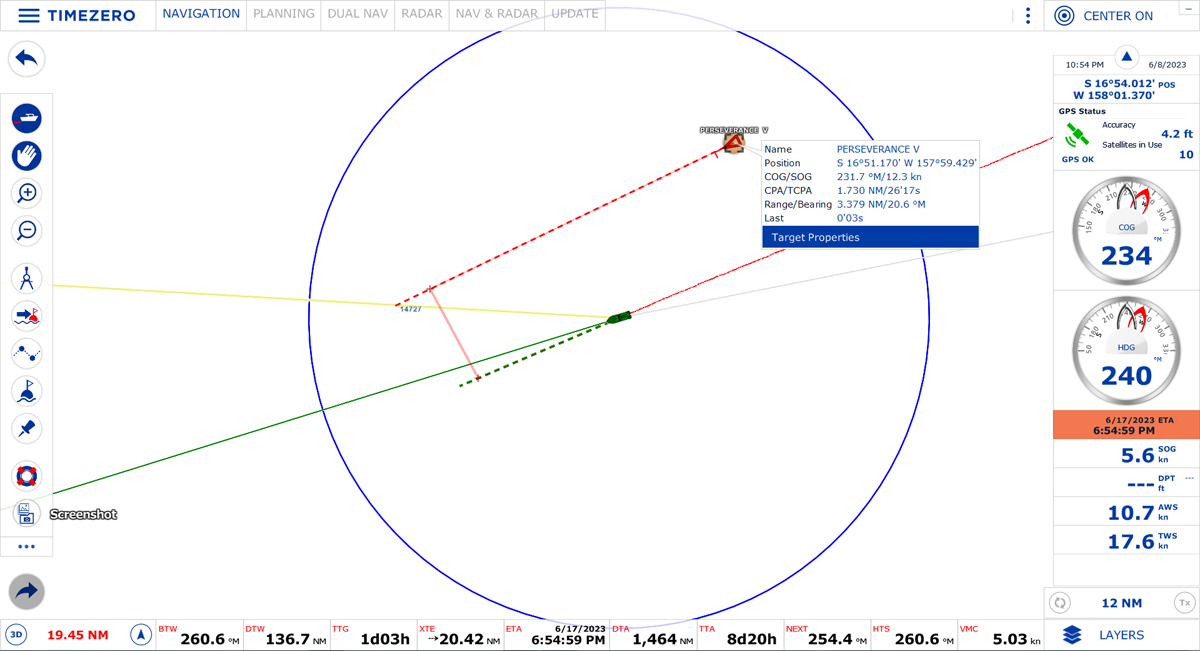

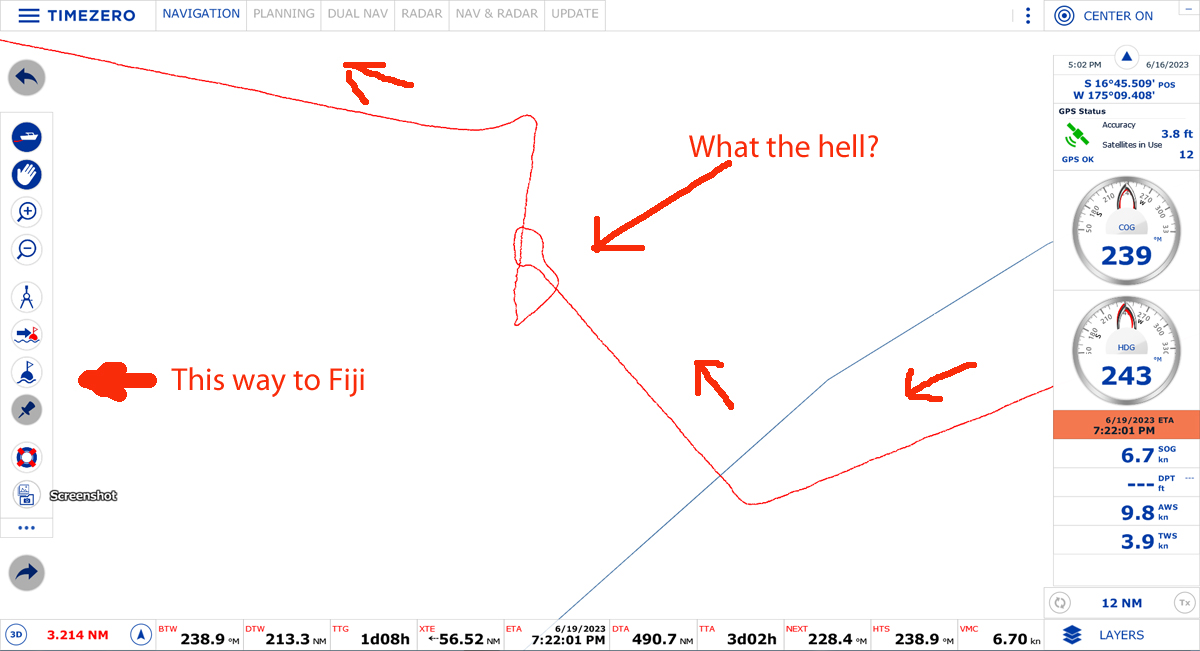

This seems like another easy one, right! The wind will rarely let you sail where you want to go. On this trip we found ourselves tacking to avoid pesky islands, doing donuts in the ocean due to lack of wind, and zigzagging around big storms. This was one of the few journeys we’ve made where we constantly had to adjust the sails. I swear the wind shifted every few hours. After the stormy weather passed, we often had trouble getting the boat to move. Yes, we do have an engine but the limitation with that is fuel. We carry enough fuel for 6 or 7 days of continuous motoring. This passage was 12 – 15 days. We need to be very selective about how much we use the engine. And don’t forget, we also need fuel for the generator to charge our batteries.

Screenshot from our ship’s computer: We saw only 2 ships the entire passage and this one decides to pass within 2 miles of us setting off all sorts of collision alarms on our boat

Screenshot from our ship’s computer: Sometimes those pesky islands are in the way and force us to tack

Screenshot from our ship’s computer: Our track is the red line – the light winds on this passage proved very frustrating

If you look at our track from Bora Bora to Fiji, it looks like we managed to sail in every direction except where Fiji was actually located. We took what should have been an easy 12-day trip with perfect winds and managed to make it 15 days.

Toward the last part of the trip, we really struggled with constant wind changes. On one day, we started out with winds on the tail coming from the east. By the afternoon the wind was on the nose coming from the west and forcing us away from Fiji. This was all the after-effects of the large stormy system we’d just sailed through. Some days we felt so close to being there but really wondered how much longer this trip was going to take.

On a side note here: why is it that manufacturers all buy their beeps from the same place? When a piece of equipment aboard the boat wishes to alert us that something’s up, it beeps. But all the equipment sounds the same. I can’t begin to tell you how many times we have gone around trying to figure out what is beeping. Sailing is noisy and trying to find a beep with old ears is not easy. Just sayin’ a little variety in sounds would be nice.

Personal Hygiene

Salespeople will attest that many people shopping for a boat will have a list of requirements. Oftentimes on the list are a shower that is separate from the rest of the head. This seems to be particularly true with women. This is a surefire sign that the person shopping for the boat has never sailed extensively on the ocean.

When you’ve had a few days of rough weather, the kind where you wedge yourself into a corner and just hang on for dear life, a shower becomes very high on your list of priorities. After sitting about in damp clothes on damp pillows the rashes start to set in. No pictures – I promise – we managed to avoid rashes. To keep the rashes at bay, a good shower is needed. This is where having an all-in-one bathroom helps.

On our boat, it is entirely possible to sit down on the toilet seat to take a shower. In fact, this is perhaps the safest way to take a shower as a person can now lift their legs and wash. If the boat were to suddenly pitch or roll, the event of falling out of the bathroom is much less if sitting. I managed not to fall out of the shower on this trip, unlike a previous passage that threw me across the boat from the shower. If the shower were separate, we’d not have this option to bathe.

On a passage, very few things feel better than a nice hot shower. A hot meal ranks up there as well. During bad weather it is grab what you can meals. Cindy is very good at provisioning the boat for all weather. She cooks for a day or two ahead to assure we have enough easy to prepare, ready meals for our trip. A good thing to have options as the weather can change quickly.

By the way, if you watched the movie True Spirit, a book-to-movie adaptation about Jessica Watson, a teen who endeavors to become the youngest person to sail nonstop alone unassisted around the world, you will see her eating a salad after being at sea for like 3-weeks. This scene had us laughing hysterically. I wonder how Hollywood thinks she managed to keep lettuce fresh for more than a week. Maybe she got a Amazon drone to drop it off. Cindy’s precooked meals, muffins and breads take a lot of prep time but are much appreciated a few days later under sail.

Being prepared ahead of time for weather changes is important. Cindy gets all of our gear ready. She also puts things we need in easy to reach places. Just prior to departure she pads cabinets for rattles so we don’t have things banging. It helps when trying to sleep if there is not banging along with all the rest of the noise. Cindy stows and ties down anything that can go flying around the boat during bad weather. She preps the boat for a storm no matter the weather because weather can change.

Make a List of Things Breaking on the Boat to Fix When the Port is Reached

Things break. Remember that generator we had an issue with? Well, part of the decision to go ahead was because we had a high-output alternator on the engine as a backup. On about day 12, when running the engine, because there was no wind at all, I notice the batteries weren’t charging. They should have been fully charge yet our gauge showed 85% capacity, and falling. Hmm. Now what?

It turns out the regulator for the alternator is shot. Without this, the alternator will not work correctly. It’s a cheap part and we don’t have a spare. We are now solely dependent on the generator to charge the batteries we need to run our systems. Systems like our GPS that tell us where we are, and where to sail. These systems also include our ship’s computer which has all of our charts detailing locations of reefs and islands. The pucker factor is now up a couple of notches. We need batteries. We still have solar – but solar needs sunshine. We still have the wind generator as well, as long as we have steady wind. Let’s hope for clear skies ahead and no generator issues.

Installing this sensitive raw water alarm saved us from what could have been an expensive repair and allowed us to keep using our generator for the passage

Speaking of the generator, do you remember me saying I belong to some online groups? On one of those groups, a guy named Eric suggested adding a gismo. It is a temperature sensor that straps to the engine exhaust hose. On marine engines, they are cooled by sea water being pumped through the engine (cars and trucks use air – radiators). The seawater goes through something called a heat exchanger. The exchanger is a series of tubes. Inside, seawater runs over tubes containing the engine coolant. This transfers some of the heat from the engine coolant to the seawater. The seawater exits the engine in something called a mixing elbow where it mixes with the exhaust gas. The pressure from the gas is used to push the water through a muffler and out of the boat. The whole purpose of my telling you this is so that you’ll understand the engines need seawater to stay within normal operating temperature range.

The gismo that Eric recommended monitors the point where the seawater exits the engine. If the seawater stops, the temperature quickly goes up and this very sensitive device gives a loud audible alarm. Yes, there is the standard light on the engine panel. However, by the time this lights up, the damage is already done to some components. The exhaust hose can be damaged and the muffler melted. Hence, the addition of Eric more sensitive and better-placed sensor. It’s sort of an early warning system.

On about day 3, I am about to take a nap and decide we should start the generator to top off the batteries. After a few minutes, a loud alarm sounds. If there were dead about us, they’d have been woken. I immediately shut down the generator. I open the engine room door, it’s hot inside. Not a good sign.

It doesn’t take long to diagnose the problem. Once again, the diesel school is paying off. This has never happened on our boat before but, we managed to get an airlock in the sea-chest. The sea-chest is a place where saltwater enters the boat, goes through a filter, and then via a manifold can be pulled by water pumps for engines, air conditioners, toilets etc. With the airlock, the pumps were unable to draw water to cool equipment.

I restart the generator. Looking over the side of the boat, I don’t see water coming out of the exhaust. Time to check the seawater pump. Remember me saying, being prepared out here really helps? We have 3 water pumps for the generator: One on the engine and two spares. Inside the seawater pump is a rubber impeller that moves the water. I have found it easier to remove the entire pump held on with 2 bolts rather than try to replace the impeller inside the pump while it is still attached to the engine. And, in my case the engine is hot. I can do this job in just a few minutes. In fact, it takes me longer to get the tools ready and pull out the box of spare generator parts from the storage locker than it does to actually do the exchange.

I restart the generator again. Eureka! Now we have good water flow. Inspecting the old pump I find the melted impeller inside. Eric’s gismo saved my muffler and stopped any further heat damage to the engine.

After this last jaunt, we have a small list of things to fix. Fortunately, most are not too expensive and can be done in Fiji as we mix in fun with work. One of the items is the GPS unit that connects to our ship’s navigation computer. It stopped working a few times during this passage. It sorta rebooted a few times and started working again each time. I have no idea what is wrong with it. We get an alarm telling us our navigation software doesn’t know our position. It’s time to float test this unit. We have three additional GPS units we can use but it irks me that this has become unreliable. Just another one of those mystery things that only happen while at sea.

If you are unfamiliar with the nautical term float test: Float test is to drop an item in the ocean; if it floats it’s broken and can’t be used. If it sinks, this means it was working just fine.

Hope it is Not Our Time to Die

Yes, there is still a little bit of fate we depend upon. We do our best to handle all that is thrown at us on an ocean passage. Preparedness, a clear level head, and lots of spare parts help. We know we have a good solid seaworthy boat and trust it. I was joking recently with a friend who said we have a good boat that is a known passage maker. I told him it was the crew I was worried about, not the boat. This last trip physically made us exhausted.

The last couple of days of the trip gave us an opportunity to rest, clean up, and even shave. When we arrived we looked like we had just returned from a nice day of sailing about the bay. Two days before, we both were wondering if we still want to do this sailing thing. We both questioned our plans to continue for the very first time. I think having the shit beat out of us by powerful squalls for three days had something to do with it.

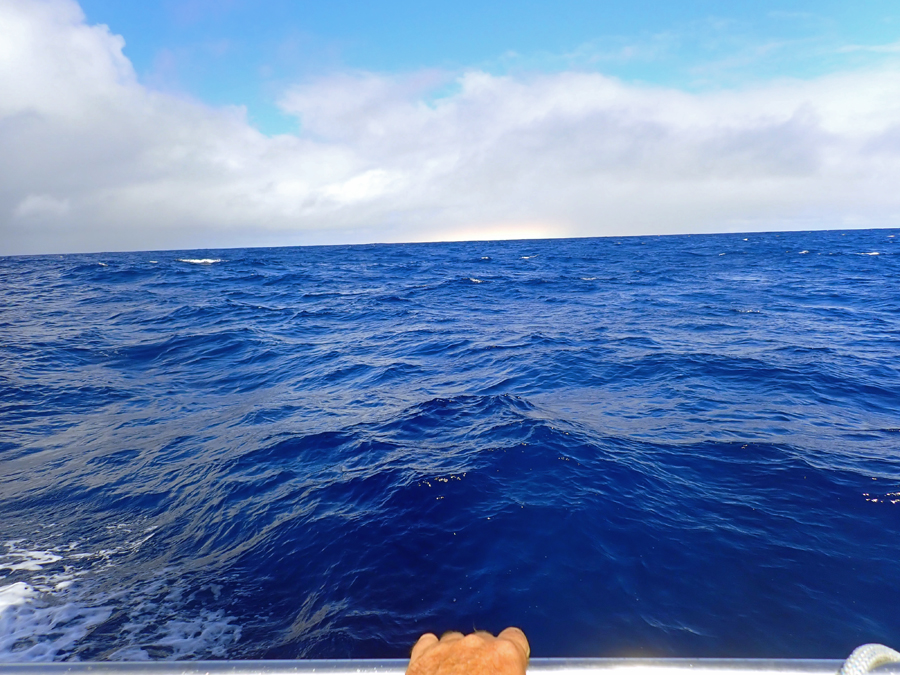

Have Fun

So, did we have fun? The short answer is, yes. On day 2 Cindy shrieked loudly as she spotted humpback whales – a real treat. They were far away but we could see big splashes, fins and tails as they surfaced. We had a couple of nights were we both managed to enjoy the stars. We see shooting stars all the time on clear nights. Everyone’s bucket list should include seeing the stars from a place where there are no light. We did enjoy some perfect sailing where the boat sailed perfectly upright across the water in ideal conditions. Though this wasn’t the norm on this trip, it has been on others. And, when it happens, we appreciated it that much more.

The best part about a trip like this is we tend to bond. Our time together has no distractions, no people, no internet, and no television. It’s just us and the boat. I have a great deal of respect for Cindy who bore the discomfort of a broken toe, sailed in horrid conditions, and still manage to keep a smile on her face. We worked well together as a team oftentimes knowing what the other person needed without speaking any words.

Tuvuca Island is our first glimpse of Fiji at sunrise in Fiji water, at last. Cindy snags this great pic – I’m sleeping

There is a massive sense of accomplishment when the port is reached after 1,890 nautical miles of sailing and 15 days at sea. We have sailed longer passages. Our longest is 29 days. Regardless of distance, arriving at a port safely is pat-on-the-back worthy. As Cindy often says, any passage completed without needing to set off the EPIRB is a successful one.

Now, here we are in Fiji. We have a few things to fix but are really excited to get out and explore new places. Was it worth getting knocked about to get here? That is for each individual to decide on their own. For us, the jury is still out. Who knows, we might fall in love with Fiji. Then, again perhaps we should take the train from now on.

Approaching Viti Levu, our destination. We actually slowed the boat down a lot so we could navigate the pass through the coral reefs during daylight hours and check in with customs during regular office hours (not having to pay for their overtime)

Cindy raises our Q (quarantine flag) indicating we are a vessel yet to clear immigration and customs. For the life of me, I don’t know how she managed this smile